Training and development refer to programs designed to help new employees adjust to the workplace successfully. In addition, they include the formal ongoing efforts of corporations and other organizations to improve the performance and self-fulfillment of their employees through a variety of methods and programs. In the modem workplace, these efforts have taken on a broad range of applications, from training in highly specific job skills to long-term professional development, and are applicable to all sorts of employees ranging from line workers to the chief executive officer. Training and development have emerged as formal corporate functions, integral elements of corporate strategy, and are recognized as professions with distinct theories and methodologies as companies increasingly acknowledge the fundamental importance of employee growth and development, as well as the necessity of a highly skilled workforce, in order to improve the success and efficiency of their organizations.

For the most part, training and development are used together to bring about the overall acclimation, improvement, and education of an organization's employees. While closely related, there are important differences between the terms and the scope of each. In general, training programs have very specific and quantifiable goals, such as operating a particular piece of machinery, understanding a specific process, or performing certain procedures with great precision. On the other hand, developmental programs concentrate on broader skills that are applicable to a wider variety of situations, such as decision making, leadership skills, and goal setting. In short, training programs are typically tied to a particular subject matter and are applicable to that subject only, while developmental programs center on cultivating and enriching broader skills useful in numerous contexts.

HISTORY OF TRAINING PROGRAMS

The apprenticeship system emerged in ancient cultures to provide a structured approach to the training of unskilled workers by master craftsmen. This system was marked by three distinct stages: the unskilled novice, the journeyman or yeoman, and finally, the master craftsman. Together, they formed an "organic" process whereby the novice "grew" into a master craftsman over a period of years.

With the onset of the Industrial Age, the training of the unskilled underwent a dramatic transformation in which vocational education and training emerged to replace the traditional apprentice system. The division of labor in an industrial factory resulted in specific job tasks that required equally specific training in a much shorter time span. As training activities grew more methodical and focused, the first recognizable modern training methods began to develop during the 19th and early 20th centuries: gaming simulations became an important tool in the Prussian military during the early 1800s and pyschodrama and role playing were developed by Dr. J. L. Moreno of Vienna, Austria, in 1910.

The early 20th century witnessed the emergence of training and development as a profession, resulting in the creation of training associations and societies, the advent of the assembly line requiring greater specificity in training, and the dramatic training requirements of the world wars. Important groups forming during this period include the American Management Association in 1923 (which began as the National Association of Corporation Schools in 1913), and the National Management Association in 1956 (which began as the National Association of Foremen in 1925). At the same time, Henry Ford (1863-1947) introduced the assembly line at his Highland Park, Michigan, plant. Because the assembly line created an even greater division of labor, along with an unprecedented need for precision and teamwork, job tasks and assignments required more highly specific and focused training than ever before.

The enormous production needs of the World War I and II created a heavy influx of new workers with little or no industrial education or skills to the workplace, thereby necessitating massive training efforts that were at once fast and effective. In particular, the heavy demand for shipping construction during World War I resulted in a tenfold increase in workers trained on-site by instructors who were supervisors using a simple four-step method: show, tell, do, check. During World War II, large numbers of trained industrial workers left their jobs to enter the armed forces, severely limiting the organizational support normally provided by coworkers in training their replacements. Heavy demands were placed on foremen and supervisors, and the training within industry (TWI) service was formed to train supervisors as instructors. Job instruction training (JIT) was employed to train defense-plant supervisors in instructing new employees in necessary job skills as quickly as possible. Other programs included job relations training (JRT), job methods training (JMT), and job safety training (JST). During this time, the American Society for Training and Development (ASTD) was formed.

By the end of World War II most companies and organizations realized the importance of training and development as a fundamental organizational tool. Training programs that originally were developed in response to national crises had become established corporate activities with long-term strategies working toward improving employee performance. In the mid1950s gaming simulations gained popularity. Trainers began giving serious consideration to the efficacy of their training programs, and interest in the evaluation of training programs grew. The 1960s witnessed an explosion of training methods as the number of corporations using assessment centers increased from one to 100 by the end of the decade. Government programs to train young men for industrial jobs, such as the Job Development Program 1965 and the Job Corps, were initiated to improve the conditions of the economically disadvantaged. New methods included training laboratories, sensitivity training, programmed instruction, performance appraisal and evaluation, needs assessments, management training, and organizational development.

By the 1970s a new sense of professionalism emerged in the training community. Training programs grew dramatically, and the ASTD produced the Professional Development Manual for Trainers. Government programs were aimed increasingly at minorities as a group and required corporations to increase their efforts to recruit minorities. With the rise of organizational development, the focus of training shifted away from the individual and toward the organization as a whole. Technological advances in training programs included the use of videotapes, satellites, and computers.

The 1980s and early 1990s saw important social, economic, and political changes that have had a profound effect on the way corporations do business, resulting in an ever increasing need for effective training. In a time of economic constraints coupled with increasing international competition, training and development programs needed to respond more quickly and effectively to technological change. Increasing governmental regulations also require a greater breadth of training programs to reflect the greater diversity of employees.

Furthermore, computers became an integral part of business and industry in the 1980s and 1990s, making knowledge of computer use essential for many workers. As a consequence, companies launched computer training and development programs to ensure that their employees possessed the needed computer skills. In addition, companies used computers as a training method known as computer-based training, relying on specially designed computer programs to impart knowledge and skills needed for a host of tasks.

CONTEMPORARY TRAINING AND

DEVELOPMENT TECHNIQUES

While new instructional methods are under continuous development, several training methods have proven highly effective and are widely used to acclimate new employee, impart new skills, and improve existing skills. They include structured on-the-job training, role playing, self-instruction, team building games and simulations, computer-based training, mentoring, and job rotation.

ON-THE-JOB TRAINING.

One of the most common and least expensive methods of training and development is on-the-job training (OJT). OJT refers to the process of learning skills while working where workers—especially new workers—obtain the knowledge and skills they need to complete their tasks through a systematic training program. Research indicates that employees acquire approximately 80 percent of their work-related knowledge and skills on the job, making consideration and implementation of successful OJT programs indispensable for employers. While OJT dates back to ancient apprenticeship programs, much 20th-century OJT remained uncodified and unstructured until the 1980s and 1990s.

The structured forms of OJT that emerged promised to remedy problems associated with unstructured OJT by relying on a planned process designed and proven to impart the necessary skills by the end of the OJT period. Nevertheless, like unstructured OJT, structured OJT involves having an experienced employee train a new employee at the work site and having the new employee receive feedback, advice, and suggestions from coworkers and trainers. Structured OJT generally assumes that new employees lack certain skills and the goal of the OJT program is to instill these skills. Therefore, employers design the training programs so that new employees do not initially perform these new tasks in order to learn. Instead, they gain knowledge and experience that will facilitate the performance of these tasks at the appropriate time and gradually work toward performing these tasks. Moreover, trainers assist and intervene at structured intervals, rather than intervening at random points in the training program as can occur with unstructured OJT.

Implementing a structured OJT program involves five basic steps: (1) analyzing the tasks and skills to be learned; (2) selecting, training, and supervising trainers; (3) preparing training materials; (4) conducting an OJT program; and (5) evaluating the program and making any necessary improvements or modifications.

ROLE PLAYING.

In role playing, trainees assume various roles and play out that role within a group to learn and practice ways of handling different situations. A facilitator creates a scenario that is to be acted out by the participants and guided by the facilitator. While the situation might be contrived, the interpersonal relations are genuine. Furthermore, participants receive immediate feedback from the facilitator and the scenario itself allowing better understanding of their own behavior.

SELF-INSTRUCTION.

Self-instruction refers an instructional method that emphasizes individual learning. In self-instruction programs, the employees take primary responsibility for their own learning. Unlike instructor- or facilitator-led instruction, trainees have a greater degree of control over topics, the sequence of learning, and the pace of learning. Depending on the structure of the instructional materials, trainees can achieve a higher degree of customized learning. Forms of self-instruction include programmed learning, individualized instruction, personalized systems of instruction, learner-controlled instruction, and correspondence study. For self-instruction programs to be successful, employers must not only make learning opportunities available, but also must promote interest in these learning opportunities. Self-instruction allows trainees to learn at their own pace and receive immediate feedback. This method also benefits companies that have to train only a few people at a time.

TEAM BUILDING.

Team building is the active creation and maintenance of effective work groups with similar goals and objectives. Not to be confused with the informal, ad-hoc formation and use of teams in the workplace, team building is a formal and methodological process of building work teams with objectives and goals, facilitated by a third-party consultant. Team building is commonly initiated to combat ineffectual group functioning that negatively affects group dynamics, labor-management relations, quality, or productivity. By recognizing the problems and difficulties associated with the creation and development of work teams, team building provides a structured, guided process whose benefits include a greater ability to manage complex projects and processes, flexibility to respond to changing situations, and greater motivation among team members.

GAMES AND SIMULATIONS.

Games and simulations are structured competitions and operational models used as training situations to emulate real-life scenarios. The benefits of games and simulations include the improvement of problem-solving and decision-making skills, a greater understanding of the organizational whole, the ability to study actual problems, and the power to capture the student's interest.

COMPUTER-BASED TRAINING.

In computer-based training (CBT), computers and computer-based instructional materials are the primary medium of instruction. Computer-based training programs are designed to structure and present instructional materials and to facilitate the learning process for the student. Primary uses of CBT include instruction in computer hardware, software, and operational equipment. The last is of particular importance because CBT can provide the student with a simulated experience of operating a particular piece of equipment or machinery while eliminating the risk of damage to costly equipment by a trainee or even a novice user. At the same time, the actual equipment's operational use is maximized because it need not be utilized as a training tool. The use of computer-based training enables a training organization to reduce training costs, while improving the effectiveness of the training. Costs are reduced through a reduction in travel, training time, amount of operational hardware, equipment damage, and instructors. Effectiveness is improved through standardization and individualization. In recent years, videodisc and CD-ROM have been successfully integrated into PC platforms allowing low-cost personal computers to serve as multimedia machines, increasing the flexibility and possibilities of CBT.

MENTORING.

Mentoring refers to programs in which companies select mentors—also called advisers, counselors, and role models—for trainees or let trainees choose their own. When trainees have questions or need help, they turn to their mentors, who are experienced workers or managers with strong communication skills. Mentors offer advice not only on how to perform specific tasks, but also on how to succeed in the company, how the company's corporate culture and politics work, and how to handle to delicate or sensitive situations. Furthermore, mentors provide feedback and suggestions to assist trainees in improving inadequate work.

JOB ROTATION.

Through job rotation, companies can create a flexible workforce capable of performing a variety of tasks and working for multiple departments or teams if needed. Furthermore, employees can cultivate a holistic understanding of a company through job rotation and can learn and appreciate how each department operates. Effective job rotation programs entail more than a couple of visits to different departments to observe them. Rather, they involve actual participation and completion of actual duties performed by these departments. In addition, job rotation duties encompass typical work performed under the same conditions as the employees of the departments experience. Because of the value some companies place on job rotation, they establish permanent training slots in major departments, ensuring ongoing exposure of employees to new tasks and responsibilities.

TYPES OF TRAINING AND DEVELOPMENT

PROGRAMS

Companies can apply these different methods of training and development to any number of subjects to ensure the skills needed for various positions are instilled. Companies gear training and development programs towards both specific and general skills, including technical training, sales training, clerical training, computer training, communications training, organizational development, career development, supervisory development, and management development. The goal of these programs is for trainees to acquire new knowledge or skills in fields such as sales or computers or to enhance their knowledge and skills in these areas.

TECHNICAL TRAINING.

Technical training seeks to impart technical knowledge and skills using common training methods for instruction of technical concepts, factual information, and procedures, as well as technical processes and principles. Likewise, sales training concentrates on the education and training of individuals to communicate with customers in a persuasive manner and inculcate other skills useful for sales positions.

COMMUNICATIONS TRAINING.

Communications training concentrates on the improvement of interpersonal communication skills, including writing, oral presentation, listening, and reading. In order to be successful, any form of communications training should be focused on the basic improvement of skills and not just on stylistic considerations. Furthermore, the training should serve to build on present skills rather than rebuilding from the ground up. Communications training can be taught separately or can be effectively integrated into other types of training, since it is fundamentally related to others disciplines.

ORGANIZATIONAL DEVELOPMENT.

Organizational development (OD) refers to the use of knowledge and techniques from the behavioral sciences to analyze existing organizational structure and implement changes in order to improve organizational effectiveness. OD is useful in such varied areas as the alignment of employee goals with those of the organization, communications, team functioning, and decision making. In short, it is a development process with an organizational focus to achieve the same goals as other training and development activities aimed at individuals. OD practitioners commonly practice what has been termed "action research" to effect an orderly change that has been carefully planned to minimize the occurrence of unpredicted or unforeseen events. Action research refers to a systematic analysis of an organization to acquire a better understanding of the nature of problems and forces within an organization.

CAREER DEVELOPMENT.

Career development of employees covers the formal development of an employee's position within an organization by providing a long-term development strategy and training programs to implement this strategy and achieve individual goals. Career development represents a growing concern for employee welfare and the long-term needs of employees. For the individual, it involves stating and describing career goals, the assessment of necessary action, and the choice and implementation of necessary actions. For the organization, career development represents the systematic development and improvement of employees. To remain effective, career development programs must allow individuals to articulate their desires. At the same time, the organization strives to meet those stated needs as much as possible by consistently following through on commitments and meeting the expectations of the employees raised by the program.

MANAGEMENT AND SUPERVISORY DEVELOPMENT.

Management and supervisory development involves the training of managers and supervisors in basic leadership skills enabling them to function effectively in their positions. For managers this typically involves the development of the ability to focus on the effective management of their employee resources, while striving to understand and achieve the strategies and goals of the organization. Management training typically involves individuals above the first two levels of supervision and below senior executive management. Managers learn to effectively develop their employees by helping employees learn and change, as well as by identifying and preparing them for future responsibilities. Management development may also include programs that teach decision-making skills, creating and managing successful work teams, allocating resources effectively, budgeting, communication skills, business planning, and goal setting.

Supervisory development addresses the unique situation of the supervisor as a link between the organization's management and workforce. It must focus on enabling supervisors to deal with their responsibilities to both labor and management, as well as coworkers, and staff departments. Important considerations include the development of personal and interpersonal skills, understanding the management process, and productivity and quality improvement.

DESIGNING TRAINING PROGRAMS

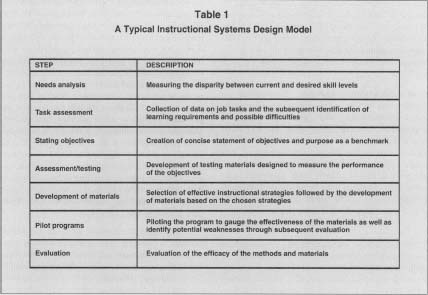

The design of training programs covers the planning and creation of training and development programs. Like the training programs themselves, the development of training programs has evolved into a profession that utilizes systematic models, methods, and processes of instructional systems design (ISD). Instructional systems design includes the systematic design and development of instructional methods and materials to facilitate the process of training and development and ensure that training programs are necessary, valid, and effective. Although the instructional design process can take on variety of sequences, the process must include the collection of data on the tasks or skills to be learned or improved, the analysis of these skills and tasks, the development of methods and materials, delivery of the program, and finally the evaluation of the training's effectiveness. Table I describes the process in greater detail.

Training and development programs often rely on the principles and theories of various behavioral sciences such as psychology and sociology. The behavioral sciences provide useful theories on individual behavior, motivations, organizational dynamics, and interpersonal relationships, which the developers of training programs can draw on when creating their programs. Similarly, the development of a distinctive

Table 1

A Typical Instructional Systems Design Model

A Typical Instructional Systems Design Model

| STEP | DESCRIPTION |

| Needs analysis | Measuring the disparity between current and desired skill levels |

| Task assessment | Collection of data on job tasks and the subsequent identification of learning requirements and possible difficulties |

| Stating objectives | Creation of concise statement of objectives and purpose as a benchmark |

| Assessment/testing | Development of testing materials designed to measure the performance of the objectives |

| Development of matenals | Selection of effective instructional strategies followed by the development of materials based on the chosen strategies |

| Plot programs | Piloting the program to gauge the effectiveness of the materials as well as identify potential weaknesses through subsequent evaluation |

| Evaluation | Evaluation of the efficacy of the methods and materials |

adult educational model has influenced the development of training programs, giving them an exclusive focus on adults. According to this model, adults learn best through goal-oriented instruction, unlike children, who learn best through instruction based on the subject matter itself. Hence, given the goal-oriented needs of adult education, the design and development of training materials have taken on a much higher level of structure and methodology than traditional methods for instructional development.

EVALUATING TRAINING PROGRAMS

Once a company implements a training program, it must evaluate the program's success, even if it has produced desired results for other companies and even if similar programs have produced desires for it. Companies first must determine if trainees are acquiring the desired skills and knowledge. If not, then they must ascertain why not and they must figure out if the trainees are failing to acquire these skills because of their own inability or because of ineffective training programs.

In order to evaluate training programs, companies must collect relevant data. The data should include easily measurable and quantifiable information such as costs, output, quality, and time, according to Jack J. Phillips in Recruiting, Training, and Retraining New Employees.

- Costs: budget changes, unit costs, project cost variations, and sales expenses.

- Output: Units produced, units assembled, productivity per hour, and applications reviewed.

- Quality: Error rates, waste, defective products, customer complaints, and shortages.

- Time: On-time shipments, production or processing time, overtime, training time, efficiency, and meeting deadlines.

Companies also can use qualitative data such as work habits, attitudes, development, adaptability, and initiative to evaluate training programs. Most companies, however, prefer to place more weight on the quantitative data previously outlined.

Furthermore, according to Phillips, companies tend to evaluate training and development programs on four levels: behavior, learning, reaction, and results. Businesses examine employee behavior after training programs in order to determine if the programs helped employees adjust to their environment; also, companies can obtain evidence on employee behavior via observation and interviews. Throughout the training process, employers monitor how well trainees are learning about the company, the atmosphere, and their jobs.

To evaluate training and development programs effectively, employers also gauge employee reactions to the programs. This feedback from trainees provides companies with crucial information on how employees perceive their programs. Using questionnaires and interviews, companies can identify employee attitudes toward various aspects of the training programs. Finally, employers attempt to determine the results of their training programs by studying the quantifiable data addressed earlier as well as by considering the employee turnover rate and job performance of workers who recently completed a training and development program.

[ Bradley T. Bernatek ,

updated by Karl Heil ]

updated by Karl Heil ]

FURTHER READING:

Craig, Robert L., ed. Training and Development Handbook: A Guide to Human Resource Development. 3rd ed. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1987.Fallon, William K., ed. AMA Management Handbook. 2nd ed. New York: AMACOM, 1983.

Goldstein, Irwin L., ed. Training and Development in Organizations. 2nd ed. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1989.

Jacobs, Ronald L., and Michael J. Jones. Structured On-the-Job Training. San Francisco: Berret-Koehler Publishers, 1995.

McCarthy, Elizabeth. "Firms Realize Training Is the Only Way to Keep Up." Sacramento Business Journal, 29 May 1998, E6.

Phillips, Jack J. Recruiting, Training, and Retraining New Employees. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1987.

"Stop Us if You've Heard This Before …: A Surgical Counterstrike against Myths and Cliches in the Training World." Training, September 1997, 24.

Tobin, Daniel R. The Knowledge-Enabled Organization. New York: AMACOM, 1998.

Source: http://www.referenceforbusiness.com

No comments:

Post a Comment