Mind the gap: China's great education divide

December 17, 2013 -- Updated 0630 GMT (1430 HKT)

STORY HIGHLIGHTS

- 15 year olds in Shanghai rank number one in the world in reading, math and science

- But critics argue exam results are not representative of the city's total student population

- Debate about the quality of education available in China's poorer, rural interior

- China released a 10-year national education reform plan in 2010 to tackle the problem

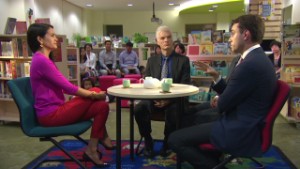

Editor's note: This month's episode of On China with Kristie Lu Stout tackles education and airs for the first time on Wednesday, December 18 at 6.30pm Hong Kong/Beijing time. For all viewing times please click here.

Shanghai (CNN) -- So, they apparently did it again.

For the second time in a decade, 15-year-olds in Shanghai have scored at the top of the PISA global education assessment, ranking number one in the world in reading, math and science.

The Chinese city has a top performing system thanks in part to the strong drive and self-belief of its students, says OECD special advisor on education policy -- and PISA survey head -- Andreas Schleicher.

"In Shanghai, you have nine out of ten students telling you, 'It depends on me. If I invest the effort, my teachers are going to help me to be successful,'" Schleicher tells me during a taping of CNN's "On China" on location in the city.

The Shanghai exam results have come under fire for shutting out the city's migrant children and not being representative of the city's total student population -- something the OECD refutes.

But one thing is for certain. The results are not representative of a nation. China as a whole does not take the PISA exam. Data on a number of Chinese cities and provinces is not yet published by PISA. China as a whole is expected to be included in the 2015 assessment.

Data from the Rural Education Action Program (REAP) at Stanford University in the United States provides a stark picture of how Shanghai's education success is not repeated in China's less wealthy, rural interior.

While 84% of high school grads in Shanghai go to college, less than 5% of China's rural poor make it to university.

High school attendance is just 40% in poor, rural areas of China.

And as they struggle with poverty and debate the opportunity cost of simply going to class, a significant number of rural students start dropping out in middle school.

Across the world's second biggest economy, the education system is vastly unequal. But incredibly, Schleicher tells me a child from a poor background in China has a better chance to be well educated than poor, rural students in other countries.

It is a huge misconception that local communities aren't invested in the education of their children and grandchildren.

Andrea Pasinetti, Teach for China

Andrea Pasinetti, Teach for China

"The learning environment you would encounter there, the quality is a lot higher than what you'd encounter in a similar context almost anywhere else in the world," he says.

Seated across from Schleicher during the "On China" panel discussion in Shanghai is Andrea Pasinetti, the founder of Teach for China -- a non-profit that brings graduates from China and the U.S. to teach at some of China's most under-resourced schools.

Pasinetti reveals a particularly bullish view on rural education in China: "A lot of these (rural) schools tend to be boarding schools. So the school provides not only a context for classroom instruction, it also provides a context for personal growth and exploration."

Pasinetti's views are distinctly out of sync with that of educator Jiang Xueqin, currently the Deputy Principal of Tsinghua University High School.

"Kids in the rural regions are at a huge disadvantage. Teachers and school are under-resourced," he says.

"The other issue is that in the rural regions, there's a lot of movement so parents move to the cities leaving their kids behind in the schools. So there isn't that parental support and guidance that kids need to thrive.

"Rural schools are under a lot of cultural stigma. No one in China believes they will succeed."

Though Jiang's assessment is in line with what has generally been reported about China's rural education challenges, Pasinetti calls it an "irresponsible perception."

"It is a huge misconception that local communities aren't invested in the education of their children and grandchildren," says the Teach for China founder.

Over the years it will become worse and worse. The rich and powerful are choosing to detach themselves from the traditional school system.

Jiang Xueqin, Tsinghua University High School

Jiang Xueqin, Tsinghua University High School

"I speak to grandmothers who are illiterate, who live often on two or three dollars a day... who would do anything and stop at nothing to make sure that the child they have in their home is able to achieve a great education.

"The big difficulty is that oftentimes, they don't know where to start."

The Chinese government is attempting to tackle the challenge. In 2010, China released a 10-year national education reform plan. Among other objectives, it plans to focus less on tests and get the best teachers into the rural communities that desperately need them.

"Every discussion you have with Chinese officials about education reform revolves around the question of equity," says Pasinetti.

But Jiang is not optimistic about the prospects for education equity in China.

"Over the years it will become worse and worse," he says. "The rich and powerful are choosing to detach themselves from the traditional school system."

Jiang sees a China where the wealthy will move education resources to a system of new private schools that cater only to them.

And that is the dark future China must avoid.

"If you don't change the school system now, you'll get people buying themselves out of it," says Schleicher.

"That's basically the challenge that China has."

No comments:

Post a Comment