Author

Harold Chen, MD, MS, FAAP, FACMG Professor, Departments of Pediatrics, Obstetrics and Gynecology, and Pathology, Director of Genetic Laboratory Services, Louisiana State University Medical Center

Background

Marfan syndrome is an inherited connective-tissue disorder transmitted as an autosomal dominant trait.

- It is noteworthy for its worldwide distribution, relatively high prevalence, clinical variability, and pleiotropic manifestations, some of which are life threatening.

- Cardinal features of the disorder include tall stature, ectopia lentis, mitral valve prolapse, aortic root dilatation, and aortic dissection.

- About three quarters of patients have an affected parent; new mutations account for the remainder.

- Marfan syndrome is fully penetrant with marked interfamilial and intrafamilial variability.

Pathophysiology

Marfan syndrome results from mutations in the fibrillin-1 (FBN1) gene on chromosome 15, which encodes for the glycoprotein fibrillin. Fibrillin is a major building block of microfibrils, which constitute the structural components of the suspensory ligament of the lens and serve as substrates for elastin in the aorta and other connective tissues. Abnormalities involving microfibrils weaken the aortic wall. Progressive aortic dilatation and eventual aortic dissection occur because of tension caused by left ventricular ejection impulses. Likewise, deficient fibrillin deposition leads to reduced structural integrity of the lens zonules, ligaments, lung airways, and spinal dura.

- Production of abnormal fibrillin-1 monomers from the mutated gene disrupts the multimerization of fibrillin-1 and prevents microfibril formation. This pathogenetic mechanism has been termed dominant-negative because the mutant fibrillin-1 disrupts microfibril formation though the other fibrillin gene encodes normal fibrillin. This proposed mechanism is evinced by the fact that cultured skin fibroblasts from patients with Marfan syndrome produce greatly diminished and abnormal microfibrils.

- FBN1 mutation causes several Marfanlike disorders, such as the mitral valve prolapse, aortic dilation, skin, and skeletal (MASS) phenotype or isolated ectopia lentis.

- Recent studies have suggested that abnormalities in the transforming growth factor-beta (TGF β )-signaling pathway may represent a final common pathway for the development of the Marfan phenotype.[1] The gene defect ultimately leads to decreased and disordered incorporation of fibrillin into the connective tissue matrix.

- The identification of mutations in transforming growth factor-beta receptor 2 (TGFβR2) in patients with Marfan syndrome type II (MFS2 mapped at 3p24.2-p25) provided direct evidence of abnormal TGFβ signaling in the pathogenesis of Marfan syndrome.

- Abnormalities in TGFβR 2 and TGFβR1 were also reported to cause a new dominant syndrome similar to Marfan syndrome; it was associated with aortic aneurysm and congenital anomalies, including Loeys-Dietz aortic aneurysm syndrome (Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man [OMIM] 609192).[1] These results define a new group of Marfan syndrome–related connective-tissue disorders, namely, TGF β signalopathies.

- A second fibrillin gene, the FBN2 gene, is responsible for the congenital contractural arachnodactyly, known as Beals syndrome

Epidemiology

Frequency

United States

Marfan syndrome affects about 1 in 10,000 individuals[3] and perhaps as many as 1 in 3000-5000.

- Estimates suggest that at least 200,000 people in the United States have Marfan syndrome or a related connective-tissue disorder.

- This makes Marfan syndrome one of the most common single-gene malformation syndromes.

International

No geographic predilection is known.

Mortality/Morbidity

Cardiovascular disease (aortic dilatation and dissection) is the major cause of morbidity and mortality.

Progression from mitral valve prolapse to mitral regurgitation, often in conjunction with tricuspid prolapse and regurgitation, is the most common cause of infant morbidity. If untreated, Marfan syndrome is highly lethal; the average age at death is 30-40 years.

Death after infancy usually involves ascending aortic dissection and chronic aortic regurgitation. Dissection generally occurs at the aortic root and is uncommon in childhood and adolescence.

Race

Marfan syndrome is panethnic.

Sex

No sex predilection is known.

Age

Marfan syndrome may be diagnosed prenatally, at birth, or well into adulthood. Neonatal presentation is associated with a more severe course than that associated with other presentations.

Most clinical features are specific to age, and some features may not manifest until relatively late in life. This feature may make diagnosis in a child difficult.

History

Marfan syndrome is currently diagnosed using criteria based on an evaluation of the family history, molecular data, and 6 organ systems. The diagnosis cannot be based on molecular analysis alone because molecular diagnosis is not generally available, mutation detection is imperfect, and not all FBN1 mutations are associated with Marfan syndrome. With the previous Berlin criteria, Marfan syndrome was diagnosed on the basis of involvement of the skeletal system and 2 other systems, with the requirement of at least one major manifestation (ie, ectopia lentis, aortic dilatation or dissection, or dural ectasia).

In 1995, a group of the world's leading clinicians and investigators in Marfan syndrome proposed revised diagnostic criteria. Known as the Ghent criteria, they identify major and minor diagnostic findings, which are largely based on clinical observation of various organ systems and on the family history. A major criterion is defined as one that carries high diagnostic precision because it is relatively infrequent in other conditions and in the general population. The Ghent criteria were intended to serve as an international standard for clinical and molecular studies and for investigations of genetic heterogeneity and genotype-phenotype correlations. The clinical diagnosis in adults should be made using the Ghent criteria, which are unreliable in children.

Revision of these nosologies was necessary because the Berlin criteria did not provide for molecular data and because they may have resulted in false diagnoses of unaffected relatives. However, the new criteria may be too stringent and may exclude Marfan syndrome in many affected patients. For example, 19% of patients whose disease was diagnosed under the Berlin criteria did not meet the Ghent criteria. When patients were screened for dural ectasia, 23% of those whose diagnosis of Marfan syndrome was established by using the Berlin criteria were considered to not have Marfan syndrome when the Ghent criteria were applied.[4]

Family history and results of molecular studies are some of the major criteria, a fact that emphasizes the need to obtain a complete family history and pedigree. The major criteria include the following:

- A first-degree relative (parent, child, or sibling) who independently meets the diagnostic criteria

- Presence of an FBN1 mutation known to cause Marfan syndrome

- Inheritance of an FBN1 haplotype known to be associated with unequivocally diagnosed Marfan syndrome in the family

- In family members, major involvement in one organ system and involvement in a second organ system

If the family and genetic histories are not contributory, major criteria in 2 different organ systems and involvement of a third organ system are required to make the diagnosis (organ system criteria described in Physical).

Clinical presentations are as follows:

- Delayed achievement of gross and fine motor milestones secondary to ligamentous laxity of the hips, knees, ankles, arches, wrists, and fingers

- A decrescendo diastolic murmur from aortic regurgitation

- An ejection click at the apex followed by a holosystolic high-pitched murmur from mitral prolapse and regurgitation

- Dysrhythmia (a primary feature)

- Abrupt onset of thoracic pain, which occurs in more than 90% of patients with aortic dissection (Other signs include syncope, shock, pallor, pulselessness, and paresthesia or paralysis in the extremities. Onset of hypotension may indicate aortic rupture.)

- Joint pain in adult patients

- Dyspnea, severe palpitations, and substernal pain in severe pectus excavatum

- Breathlessness, often with chest pain, in spontaneous pneumothorax

- Visual problems, possibly loss of vision, from lens dislocation or retinal detachment (The most common refractory errors are myopia and amblyopia.)

Physical

At this time, the diagnosis of Marfan syndrome remains mainly clinical.

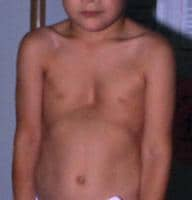

Skeletal findings

Affected patients are usually taller and thinner than their family members. Their limbs are disproportionately long compared with the trunk (dolichostenomelia). Arachnodactyly is a common feature. See the images below for examples.

Adult with Marfan syndrome. Note tall and thin build, disproportionately long arms and legs, and kyphoscoliosis.

Adult with Marfan syndrome. Note tall and thin build, disproportionately long arms and legs, and kyphoscoliosis. Arachnodactyly.

Arachnodactyly.

Although the vast majority of patients are diagnosed before the age of 10 years, few present with the 4 skeletal criteria, which are developed later in life.[5]

Major criteria include the following:

- Reduced upper-to-lower body segment ratio (0.85 vs 0.93) or arm span–to-height ratio greater than 1.05: Arms and legs may be unusually long in proportion to the torso.

- Positive wrist (Walker) and thumb (Steinberg) signs: Two simple maneuvers may help demonstrate arachnodactyly. First, the thumb sign is positive if the thumb, when completely opposed within the clenched hand, projects beyond the ulnar border. Second, the wrist sign is positive if the distal phalanges of the first and fifth digits of one hand overlap when wrapped around the opposite wrist (see the images below).

Positive wrist (Walker) sign.

Positive wrist (Walker) sign. Positive thumb (Steinberg) sign.

Positive thumb (Steinberg) sign. - Scoliosis greater than 20°: More than 60% of patients have scoliosis. Progression is most likely with curvature of more than 20° in growing patients.

- Reduced extension of the elbows (< 170°)

- Medial displacement of the medial malleolus, resulting in pes planus: Pes planus is best diagnosed by examining the foot from behind. A valgus deviation of the hindfoot indicates pes planus.

- Protrusio acetabuli of any degree: This is a deformity of the hip joint in which the medial wall of the acetabulum invades the pelvic cavity with associated medial displacement of the femoral head and is ascertained using radiography. Protrusio acetabuli affects 31-100% of patients to varying degrees.[6] Clinical manifestations include hip joint stiffness and progressive limitation in activity related to joint pain, a waddling gait, limited range of motion, flexion contracture, a pelvic tilt with a resulting hyperlordosis of the lumbar spine, and eventual osteoarthritic changes.[7] Local progressive protrusion can lead to early hip pain and osteoarthritis.

Minor criteria are as follows:

- Pectus excavatum of moderate severity

- Scoliosis less than 20°

- Thoracic lordosis

- Highly arched palate

- Dental crowding

- Typical facies (dolichocephaly, malar hypoplasia, enophthalmos, retrognathia, down-slanting palpebral fissures)

For the skeletal system to be involved, at least 2 major criteria or 1 major criterion plus 2 minor criteria must be present.

Ocular findings

The major criterion is ectopia lentis. About 50% of patients have lens dislocation. The dislocation is usually superior and temporal. This may present at birth or develop during childhood or adolescence.

Minor criteria for the ocular system include the following:

- Flat cornea (measured by keratometry)

- Increased axial length of the globe (measured by ultrasound)

- Cataract (nuclear sclerotic) in patients younger than 50 years

- Hypoplastic iris or hypoplastic ciliary muscle that causes decreased miosis

- Nearsightedness regardless of whether the lens is in place: The most common refraction error is myopia due to elongated globe and amblyopia.

- Glaucoma (patients < 50 y)

- Retinal detachment

At least 2 minor criteria must be present.

Cardiovascular findings

Cardiovascular involvement is the most serious problem associated with Marfan syndrome.

Major criteria include the following:

- Aortic root dilatation involving the sinuses of Valsalva: The prevalence of aortic dilatation in Marfan syndrome is 70-80%. It manifests at an early age and tends to be more common in men than women. A diastolic murmur over the aortic valve may be present

- Aortic dissections involving the ascending aorta

Minor criteria are listed as follows:

- Mitral valve prolapse (55-69%): Midsystolic clicks may be followed by a high-pitched late-systolic murmur and, in severe cases, a holosystolic murmur.

- Dilatation of proximal main pulmonary artery in the absence of peripheral pulmonic stenosis or other cause.

- Calcification of mitral annulus (patients < 40 y)

- Dilatation of abdominal or descending thoracic aorta (patients < 50 y)

For the cardiovascular system to be involved, a minor criterion must be present.

Pulmonary findings

For the pulmonary system, only minor criteria are noted. For the pulmonary system to be involved, a minor criterion must be present.

Minor criteria include the following:

- Spontaneous pneumothorax (about 5% of patients)

- Apical blebs on chest radiography

Skin and integumentary findings

For skin and integument, only minor criteria are noted. For the skin and integument system to be involved, a minor criterion must be present.

Minor criteria include the following:

- Recurrent or incisional hernia

Dural findings

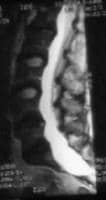

For the dura, only one major criterion is defined: Dural ectasia must be present and confirmed using CT or MRI.

Dural ectasia is an enlargement of the dural sac and the spinal canal and sometimes with enlarged nerve sleeves.[8] Dural ectasia is a common feature of Marfan syndrome. The prevalence of dural ectasia among patients with Marfan syndrome is 65-92%

Dural ectasia is defined as a ballooning or widening of the dural sac, often associated with herniation of the nerve root sleeves out of the associated foramina.

Dural ectasia most frequently occurs in the lumbosacral spine

The most common clinical symptoms are low back pain, headache, weakness, and loss of sensation above and below the affected limb, occasional rectal pain and pain in the genital area.[8] The symptoms are aggravated mainly in the supine position and are relieved by lying on the back.[9]

Severity appears to increase with age, supporting the hypothesis that a weakened dural sac expands from the cumulative effect of increased intrathecal pressure at the base of the spine from upright posture. Less than 20% of patients have serious dural ectasia.

Dural ectasia can also be associated with conditions such as Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, neurofibromatosis type 1, ankylosing spondylitis, trauma, scoliosis, or tumors.

Key issues in the assessment of Marfan syndrome [10]

Diagnosis or exclusion of Marfan syndrome in an individual should be based on the Ghent diagnostic nosology.

The initial assessment should include a personal history, detailed family history and clinical examination including ophthalmology examination and transthoracic echocardiogram.

The aortic diameter at the sinus of Valsalva should be related to normal values based on age and body surface area.

The development of scoliosis and protrusio acetabulae is age dependent, commonly occurring following periods of rapid growth. Radiography is indicated for these features, depending on age, if a positive finding confirms the diagnosis of Marfan syndrome.

A pelvic MRI scan to detect dural ectasia is indicated if a positive finding would make the diagnosis of Marfan syndrome.

The Ghent nosology cannot exclude Marfan syndrome in children, because of the age-dependent penetrance of many features.

Younger patients with a positive family history but unsuccessful DNA testing and insufficient clinical features to fulfill the diagnostic criteria, and younger patients with no family history who miss fulfilling the diagnostic criteria by one system only should be offered further clinical evaluations at least until age 18 years, or until a diagnosis can be made.

Family history of aortic aneurysm may represent a disorder such as familial thoracic aortic aneurysm such that the use of the Ghent nosology to assess risk in relatives is inappropriate.

Revised Ghent criteria for the diagnosis of Marfan syndrome and related conditions [11, 12]

Abbreviations are as follows:

- Ao - Aortic diameter at the sinuses of Valsalva above indicated Z-score or aortic root dissection

- EL - Ectopia lentis

- ELS - Ectopia lentis syndrome

- FBN1 - Fibrillin-1 mutation

- FBN1 not known with Ao -FBN1 mutation that has not previously been associated aortic root aneurysm/dissection

- FBN1 with known Ao -FBN1 mutation that has been identified in an individual with aortic aneurysm

- MASS - Myopia, mitral valve prolapse, borderline (Z< 2) aortic root dilatation, striae, skeletal findings phenotype

- MFS - Marfan syndrome

- MVPS - Mitral valve prolapse syndrome

- Syst - Systemic score

- Z - Z-score

In the absence of a family history, the following is noted:

- (1) Ao (Z ≥ 2) AND EL = MFS

- (2) Ao (Z ≥ 2) AND FBN1 = MFS

- (3) Ao (Z ≥ 2) AND Syst (≥7 points) = MFSa

- (4) EL AND FBN1 with known Ao = MFS

In the presence of a family history (EL with or without Syst AND with an FBN1 not known with Ao or no FBN1 = ELS Ao (Z < 2) AND Syst (≥5) with at least one skeletal feature without EL = MASS MVP AND Ao (Z < 2) AND Syst (> 5) without EL = MVPS):

- (5) EL AND FH of MFS (as defined above) = MFS

- (6) Syst (≥7 points) AND FH of MFS (as defined above) = MFSa

- (7) Ao (Z ≥ 2 above 20 years old, ≥3 below 20 years) + FH of MFS (as defined above) = MFS

Systemic score (maximum total = 20 points; score ≥7 indicates systemic involvement)

- Wrist AND thumb sign – 3 (Wrist OR thumb sign – 1)

- Pectus carinatum deformity – 2 (pectus excavatum or chest asymmetry – 1)

- Hindfoot deformity – 2 (plain pes planus – 1)

- Pneumothorax – 2

- Dural ectasia – 2

- Protrusio acetabuli – 2

- Reduced US/LS AND increased arm/height AND no severe scoliosis – 1

- Scoliosis or thoracolumbar kyphosis – 1

- Reduced elbow extension – 1

- Facial features (3/5) – 1 (dolichocephaly, enophtalmos, downslanting palpebral fissures, malar hyoplasia, retrognathia)

- Skin striae – 1

- Myopia > 3 diopters – 1

- Mitral valve prolapse (all types) – 1

Causes

Marfan syndrome is caused by mutations in FBN1 gene located on chromosome 15q21.1 and, occasionally, by mutation in TGFβR1 or TGFβR2 gene located on chromosome 9 and on chromosome 3p24.2-p25, respectively.

More than 500 fibrillin gene mutations have been identified. Almost all of these mutations are unique to an affected individual or family. Different fibrillin mutations are responsible for genetic heterogeneity. Phenotypic variability in the presence of the same fibrillin mutation suggests the importance of other, yet-to-be-identified factors that affect the phenotype.

Despite intensive international efforts, genotype-phenotype correlations have not been made, with the exception of an apparent clustering of neonatal mutations between exons 24 and 32 of FBN1. The neonatal Marfan syndrome represents the most severe end of the clinical spectrum of the fibrillinopathies and is associated with mutations in exons 24–32.[13] Affected individuals are generally diagnosed at birth or shortly thereafter. Unique features include joint contractures, "crumpled" external ears, and loose skin. Congestive heart failure associated with mitral and tricuspid regurgitation is the main cause of death, whereas aortic dissection is uncommon. Survival beyond 24 months is rare.[14]

- Genotype-phenotype correlations in Marfan syndrome have been complicated by the large number of unique mutations reported, as well as by clinical heterogeneity among individuals with the same mutation.

- Mutations in the FBN1 gene have also been found in patients with other fibrillinopathies.

- Identifying a given mutation is currently of limited value in establishing a phenotype or providing a prognosis.

Marfan syndrome is known as an autosomal dominant connective tissue disorder. However, recently a family was reported to have homozygosity for a FBN1missense mutation and molecular evidence for recessive Marfan syndrome.[15]This obviously has implications for genetic counseling and for molecular diagnosis.

No comments:

Post a Comment